Your Custom Text Here

charles garabedian

roberto chavez

eduardo carrillo

louis lunnetta

lance richbourg

marvin harden

joan maffei

ben sakoguchi

maxwell hendler

james urmston

marcel cavalla

jan stussy

les biller

aron goldberg

edmund teske

ray brown

ed newell

charles garabedian

roberto chavez

eduardo carrillo

louis lunnetta

lance richbourg

marvin harden

joan maffei

ben sakoguchi

maxwell hendler

james urmston

marcel cavalla

jan stussy

les biller

aron goldberg

edmund teske

ray brown

ed newell

• Charles Garabedian • collection / Sakoguchi ^

• Charles Garabedian • collection / Garabedian Family Trust ^

• Roberto Chavez • collection / Artist ^

• Eduardo Carrillo ^

• Louis Lunetta• LIFE Magazine May 20, 1957 p. 95 ^

• Lance Richbourg, Marvin Harden & Joan Maffei at Ceeje ^

• Lance Richbourg • collection / Sakoguchi ^

• Lance Richbourg ^

• Marvin Harden • collection / Sakoguchi ^

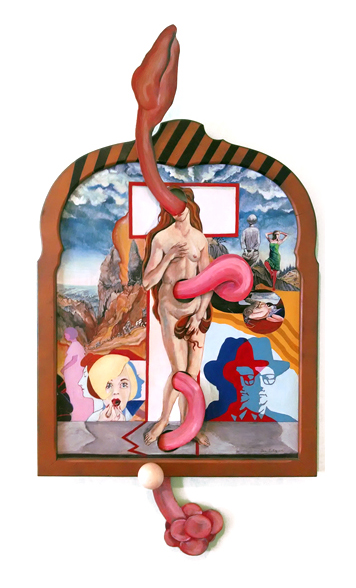

• Joan Maffei • collection / Sakoguchi ^

• Joan Maffei • collection / Sakoguchi ^

• Ben Sakoguchi ^

• Maxwell Hendler • collection / Sakoguchi ^

• James Urmston ^

• Marcel Cavalla • collection / Sakoguchi ^

• Marcel Cavalla ^

• Jan Stussy ^

• Jan Stussy • collection / Woodbury University ^

• Les Biller • collection / Artist ^

• Les Biller • collection / Kirsten Biller ^

• Aron Goldberg • collection / Sakoguchi ^

• Edmund Teske ^

• Edmund Teske ^

Excerpts from Oral history interview with Charles Garabedian, 2003 Aug. 21-22, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, conducted by Anne Ayres:

MS. AYRES: Were most of the artists involved with Ceeje [Gallery] from UCLA?

MR. GARABEDIAN: Well, yes, they were. There were a couple of oddballs that came out of Ceeje. Do you know Ed Newell? Ed showed there. He was definitely not out of UCLA. They had a Philip Pearlstein drawing show. I met him later in New York and he absolutely denied ever having shown at Ceeje.

[Ms. Ayres shows Mr. Garabedian a catalogue] Where did you get this thing? Oh, this was that show [Ceeje Revisited].

MS. AYRES: It’s not from the period.

MR. GARABEDIAN: All these people went to UCLA.

MS. AYRES: Would you name them while we’re looking at them? You’re in the picture. We’re looking at the cover of the Ceeje Revisited catalogue.

MR. GARABEDIAN: This is Lance Richbourg, Jim Urmston, Les Biller, Bob Chavez, and Ed Carrillo [Eduardo Carrillo].

MS. AYRES: And Ed Carrillo. In that catalogue, Fidel Danieli – we all remember quips that quote, “If Ferus Gallery was the cutting edge of L.A. modernism, Ceeje was the ragged edge, and several of the artists could parody their own situation and bill themselves as the rear guard.” I believe there was an exhibition at Ceeje called Six Painters of the Rear Guard. I imagine that rear guard was a good joke.

MR. GARABEDIAN: Yes. You bet.

MS. AYRES: Did the group at Ceeje feel they were conservative in the sense of upholding a figurative tradition?

MR. GARABEDIAN: No. They looked at themselves primarily as independent artists.

…MS. AYRES: This was part of the mystique of the Ferus Gallery though, too. It’s highly, highly professionalized for all the romance that has grown up around the Ferus Gallery. The more romantic people were probably with the Ceeje or with other galleries.

MR. GARABEDIAN: Well, we like to say the stupider people were with Ceeje.

MS. AYRES: But the less career-driven, maybe?

MR. GARABEDIAN: Yes, definitely. Well, I think, you could say that most of them there were driven by the idea that they thought that probably the end was teaching at some university or school or something and if they were good enough they would succeed beyond that, but they didn’t see the world of galleries and contemporary art out there while they were in school. Didn’t see it or somehow didn’t connect with it, or didn’t see fine art or the selling of art as a way of making a living.

…MR. GARABEDIAN: It’s an absolutely amazing story, I think. There’s a person who should be interviewed—Peter Goulds—just to see how he did it. I think it’s amazing how Larry did it too. I can’t understand that either, but somebody said, “Well, Larry’s got a great eye.”

MS. AYRES: Well, a great eye. They say that about Doug Chrismas. I mean, they’ve said that about other famous L.A. galleries.

MR. GARABEDIAN: They never said it about the Ceeje Gallery. The directors of the Ceeje Gallery were two great homosexuals: Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome.

MS. AYRES: Interior decorators?

MR. GARABEDIAN: Yes. And one of their people was Ellie Neil, who is now Ellie Coppola. Ellie was doing decorative work with them, and down the street from Ceeje was the Esther Robles Gallery. Was it Esther Robles? No, it wasn’t. It was Joan Ankrum Gallery, one day she had a Morris Broderson show. Morris Broderson was an artist who was very popular in the early ‘60s. They had so much work that they needed the two galleries to show all the Broderson work. They asked to rent the Ceeje space while it was still a decorator’s space. All the Broderson work sold. Everything sold out of the show, and Jerry and Cecil said, “God, we’re in the wrong business.” So they asked Ellie, “Do you know any painters? We want to turn this into a fine arts gallery.” That was the birth of Ceeje.

MS. AYRES: We’re looking at the catalogue of Ceeje.

MR. GARABEDIAN: We were the four artists in the first show.

MS. AYRES: And we’re looking at a photograph of Chas Garabedian, Ed Carrillo, Bob Chavez, and Louie Lunetta.

MS. AYRES: Were they all in the Rear Guard show too?

MR. GARABEDIAN: Yes.

MS. AYRES: So what do you think people mean when they say a dealer or even a critic has a good eye? Does this means an educated eye, an intuitive eye to trends, or an eye to some elusive thing known as quality?

MR. GARABEDIAN: I think it’s all of those together. Some people would say they don’t have any sense of real – but they have the sense of quality, what’s pertinent, what’ll sell, and they have to know art.

MS. AYRES: And yet the Ceeje Gallery lasted almost 10 years.

MR. GARABEDIAN: They lasted through enthusiasm. They just had incredible enthusiasm. They were great guys. The two of them were just so nuts you couldn’t believe it.

MS. AYRES: So a good eye doesn’t necessarily imply enthusiasm.

MR. GARABEDIAN: They loved what they were doing.

by Fidel Danieli

Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery

April 10- May 13, 1984

Foreword and Acknowledgment

The sum total of Ceeje Gallery’s contribution to the Los Angeles art situation is probably inestimable. Like many other enterprises in the retail sales of local art, it opened its doors for business, gave it a fair go, survived less than a decade and closed. It created a ripple of sorts by being a controversial center of non-mainstream art, but beyond that it had a different kind of spirit from the other galleries of the 1960’s in every area. Located at the north end of La Cienega Boulevard’s “gallery row,” it was isolated blocks beyond the clustered dealers closer to Melrose. It definitely had a different kind of look- an inviting manner. No blank or intimidating facade, no rabbit warren arrangement of rooms, no indifferent secretary to screen out the hoi polloi, no secret blue chip stock in the shrouded back rooms. There were no solemn veiled mysteries of art only for the connoisseur, no slick salesperson or world weary entrepreneur speaking only with the truly anointed. The look-better yet the feel- of Ceeje was of direct, enthusiastic freshness. An open, uncovered front window decorated with an artist’s major work or specially executed mural welcomed in the southwestern sun and permitted the visitor a preview glimpse. The room was a spacious long one, lined on one side by a built-in bench that encouraged contemplation and conversation. The dealers’ desk was screened only by a partition dividing the space into two areas. Moreover, the owners, Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome, were almost always there to share their faith in their artists.

The Ceeje gallery was opened as a crafts gallery in 1959 and was an outgrowth of Cecil Hedrick’s ceramic work in the area of architectural commissions. Hedrick’s background included a BA degree and postgraduate work in fine arts at the University of California, Los Angeles and several years of teaching. Jerry Jerome was involved in television and was a theater arts major at UCLA. It was a friend in public relations, Florence Mullen, who suggested the joining of their first initials for the gallery’s unique name. Another associate was Eleanor Neil (Coppola), whose contacts led to support of several of the artists who became the most widely recognized.

Despite the knowledge that few local galleries concentrated on Southern California art in preference to safer, tested European and East Coast examples, and that most major collectors bought in New York, they committed themselves to a core group of artists who came to exemplify the identifiable Ceeje image. This art was figurative with a tendency toward the expressionist and the surreal; it possessed an enormous degree of visual excitement and energy, and was most certainly not in vogue or fashion. They admired artists who, as they describe themselves, “were their own people, renegades and mavericks,” and who were “their own mainstreams.” They concentrated on artists who were free spirits, as free as themselves. From their own experiences in art and theater they admired directed spontaneity and unplanned discipline. the improvisational, the varied and the diverse, the non-limited were their ideals.

Ceeje’s dedication to their artists and their belief in Los Angeles art is exemplified by their exhibition record vis a vis New York. Few East Coast artists were shown- Philip Pearlman’s first two West Coast shows being notable exceptions. On the other hand, they did expand and operated a New York branch for several years (1965-67) and drew intrigued recognition and approval of their efforts from notable New York dealers. Then the bloom of the scene faded, the market slumped, the artists became discouraged. In 1967 the dealers, feeling “we had made our mark,” closed the New York branch of Ceeje Gallery. They had, however, promised and delivered exposure and promotion. They intuited what was unique about the L.A. art situation, gambled and waited. A quarter century later this exhibition validates many of their choices, both in their belief in the talent of their artists and their total commitment to expressive figurative styles.

The majority of their artists were young, and enrolled in the masters’ program at UCLA. This in an era when the tacit standards of gallery representation indicated that one should at least be in his mid-thirties and have a string of juried show acceptances and a grant or award or two on his record. It is easy to forget that into the 1970s the general opinion was held that artists had to prove themselves elsewhere before even thinking they might someday be part of a local gallery’s stable. The number of the university’s painters who had their inaugural solo show or subsequent second or third exhibits at Ceeje is impressive and includes Les Biller, Eduardo Carrillo, Roberto Chavez, Charles Garabedian, Marvin Harden, Louis Lunetta, joan Maffei, Lance Richbourg, Ben Sakoguchi, Jim Urmston and several others. It must be noted, however, that vigor, whether youthful or more senior, was the dealers’ criterion. Artists at mid-career or even older were also displayed and later on many members of the UCLA faculty were included. And though the emphasis was on painting, sculptors, assemblage artists and photographers such as Barbara Morgan and Edmund Teske also had their turn.

In contrast to the certified products and serial images of other galleries, the shows here most often included diverse media and wildly divergent sizes. Drawings, prints, painted reliefs, three-dimensional constructions, small and monumental paintings all jostled for attention in one-person and group theme shows. The formality of aesthetic distance was destroyed further by presentation. Framing was appropriately eclectic and probably determined by relative poverty. Rude and handsome trim contrasted with kitschy charity store frames. One would not be surprised to find that works were painted on found scraps or made to fit frames that were readymade or from the dime store. No limits on what was saleable seemed to have been set; no holds were barred in wrestling for the audience’s attention. Even such ephemera as exhibit announcements were totally personal, as opposed to the standardized format imposed on mailers and brochures sent out by other dealers. No formality here. Announcements varied from outsized type on colored paper to the reproduction of the hand-lettered and freely brushed, with an occasional archly posed and humorous photographed setup.

No clearer example of these dealers’ open approach (given their stylistic dedication to UCLA and the figurative) is evidenced by the ethnicity of their artists. Long before equal opportunity became a major issue and a legal mandate, their stable included artists whose heritages spanned the Mediterranean to Armenia, Hispanics, a Black, an Asian. Women artists , too, played a regular role in solo and group exhibitions. There was no decision to maintain a balance or ratio of minorities and women, it was, they explain, simply a matter of developing associations wherein the artists, their kin and their families (to a lesser or greater degree) became part of the Ceeje “family.” For Hedrick and Jerome there was no boundaries; they did not think that way.

The lineage of New York mainstream art runs in a series of links and twists that most acknowledge. European modernism gave rise to Abstract Expressionism; then came the opening provided by Rivers, Johns, Rauschenburg and Kaprow in the mid-to late-1950’s. There followed the multiplication of styles in the 1960’s as Pop, Geometric, Post-Painterly. Optical, Minimal, Environmental, New Realism and Photo realism, Conceptual,etc. To these, Los Angeles proponents and propagandists asserted adding expressive ceramic,ic work, repeated series of hard edged or geometric styles in nearly identical works, and a careful attention to surfaces and detail using industrial materials and hand- polished craft. Evidently only for local consumption would be any continuation of the rendering of traditional subjects. Still lives, interiors, portraits, figurative works in any non-academic style seemed a dead end or an exhausted vein. The irony is that around 1960 a group of Southern California art students emerged and coalesced around the Ceeje Gallery, and 20 years ahead of its current acceptance by the European and New york art world, they would turn the figurative tradition back in the direction of the personally symbolic. the intimate and autobiographical, the anecdotal and narrative, the mythic. They ransacked art history, as have more recently Germans, Italians and Americans, and turned their attention to the perennial image-making power of emotional illusionism. Their all-consuming interests ran the range from direct naiveté and primitivism of sophisticated ethnic and folk art to the obstinate delineations of Rousseau and the loving care of early Flemish masters. Attractive, too, seemed to be the make believe realism of Uccello and the horrors of Bosch. Pre- Columbian and African sculpture were no strange manifestations. Their surrealism was the mysterious and compulsively hypnotic sort drawn from the synthetic worlds of medieval art, De Chirico and Magritte. Those favoring a painterly attack were inspired by the German Expressionists with both the bold dislocations and heavy outline of Beckmann a clear favorite. Those attracted to full volume drew on everyone, from cowboy artists like Remington and Russell to the mechano-men of Leger and the bombastics of the ’20’s Mexican muralists, Rivera and Siqueiros. They were willfully awkward or private, purposely clumsy or unabashedly direct. If Ferus Gallery was the “cutting edge” of LA modernism, Ceeje was the ragged edge and several of the artists could parody their own situation and bill themselves as the “rear guard.”

Hedrick and Jerome felt they were being avant guard in espousing these young radicals and it has taken over a decade-more like two- to prove that their vision was right. Their feelings were honest and true.

by Susan B. Larsen

Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery

April 10- May 13, 1984

Foreword and Acknowledgment

Among the paradoxes of recent history is our perception of the 1960’s as a time of political and social upheaval supporting a restrained, Apollonian art. Minimalism with its pristine form and desire for visual and conceptual clarity had a significant impact

on both coasts while the smooth, mirrored surfaces of Pop Art reflected but did not necessarily confront the heated controversies of the era. Cool art for an overheated world may have served as a visual and emotional refuge fulfilling a need for minimalism’s controlled, selective sensuous experience and physical certitude. Pop Art made us even more aware of a psychological and physical media-scape which held life’s most vivid experience at arm’s length. As that period recedes in time and memory and becomes the province of cultural historians, it seems that two things are happening. The clichés of the period gain in authenticity even as a wealth of new information serves to contradict or at least counterbalance them.

Many experienced and remember the healthy, if short lived, renaissance that Los Angeles enjoyed during the 1960’s. Recent attempts to document and reconstruct the period have centered around the efforts of a few galleries, the Ferus,the Landau, Dwan and Wilder and the advent of major museum programs such as those of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the poignant tenure of the Pasadena Museum of Modern Art with its high hopes and brief but important period of national prominence.

A number of individual artists, also part of that renaissance, did not fit into the mainstream, their origins largely unexplained, ignored or forgotten. The expressionist, figurative style they practiced has gained new interest and prominence with the revival of figurative art on the international scene, prompting a reexamination of the work of several remarkable individuals. One of the mainstays of the Los Angeles art community from 1961 to 1970 was the Ceeje Gallery at 968 La Cienega Boulevard named for its co founders Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome. Ceeje and its artists were out-of-phase with much of Los Angeles art of the time but it achieved a degree of prominence and affectionate regard for its “humanity, humor and iconoclasm.”1 The work shown at Ceeje was predominantly figurative, the artists cross-section of Los Angeles ethnicity, un-cool, self-expressive and unpredictable.

Exhibitions at Ceeje were carefully installed with attention to the needs of the artist and audience, yet the gallery had a festive, improvisational character and Hedrick and Jerome assumed a posture which was not authoritative but frankly experimental. Then as now, the work shown at Ceeje was vital, enjoyed by sophisticated and unsophisticated audiences but placed solidly outside the mainstream by Los Angeles critics, curators and collectors, hence misunderstood and as it turns out, undervalued.

This “working man’s gallery”2 neither fashionable nor highly profitable at the time, helped to sustain such gifted artists as Eduardo Carrillo, Charles Garabedian, Roberto Chavez, Joan Maffai, Ed Newell, Lance Richbourg and others during a period of high hopes and expectations realized by only a few. For the vast majority of Los Angeles artists, including most of those at Ceeje, several more decades of struggle and development lay ahead once the Los Angeles Renaissance had abated.

At the outset Ceeje seemed to have an identifiable style and spirit which announced itself in the 1961-62 season with the exhibition “Four Painters: Garabedian/ Chavez/ Carrillo/ Lunetta.” Henry Seldis, senior critic for the Los Angeles Times, noted the exhibition’s “disturbing eroticism” and believed the artists were casting a nostalgic glance toward Mexico.”3 Confusion reigned concerning the ethnicity of many Ceeje artists. The Mexican surnames of Chavez and Carrillo were prominent but both were born in the United States and while proud of their ethnic origins they were as typical of the population of Los Angeles as any of the artists who showed at Ferus or Landau. Lunetta, Italian-American, and Garabedian, Armenian-American, were also long-term Los Angeles residents but were grouped with all the other Ceeje artists in one colorful ethnic blur. Hedrick and Jerome often heard the remark, “Oh, you’re the gallery that shows Mexican artists.”4 A more precise observer would have noted the remarkable ethnic range of Ceeje which represented a variety of young contemporaries residing in Los Angeles, including many ethnic minorities and women. The freewheeling, iconoclastic nature of Ceeje was evident in that first four-man show and subsequent exhibitions brought Lance Richbourg, Joan Maffai, Ed Newell, Aron Goldberg, Ben Sakoguchi and photographer Edmund Teske into prominent positions within the gallery.

Charles Garabedian at age thirty eight was the oldest of the four artists showing at Ceeje in 1962. All were recent graduates of UCLA’s lively art department and had a great deal in common, but Garabedian’s maturity gave even his early work a depth and complexity of emotion which would distinguish his art. He was a remarkably awkward painter, as aware as anyone of the lapses in his drawing and the distance he had to go to close the gap between ambition and result. Garabedian appeared to accept this in good humor indeed to feed off of his awkwardness as in the inventive and self-parodying work “Self-Portrait as a Carpenter” (1964) exhibited at the Ceeje with its roughhewn, strangely constructed frame. William Wilson observed that the artist seemed to “tell us he sees himself as an awkward craftsman who dreams beyond his ambition.” Wilson went on to describe the work as “strikingly ill-made.”5 It must have seemed so to the artist because Garabedian repeated the image of himself as an obsessive carpenter in his own Family Portrait which shows the artist building a grand but unfinished structure to house his wife and daughter.

We see garabedian as the protagonist in another of his early paintings shown at Ceeje, the Self-Portrait With Cabinet (1964). Here the artist stands in a theatrical pose, armed like a Roman gladiator with palette and brushes, dressed in a wrapped garment, either toga, smock or bathrobe, eyes blazing with excitement. It is absurd and wonderful at the same time, full of disturbing aspects such as the empty cabinet’s wide open doors, the artists hairy chest and exaggerated physiognomy, his disconnected thumb and undulating shoe.

Although their work might have been unrefined at the time, the young artists of Ceeje would never have characterized themselves by the timid word, “emerging.” Instead, they burst on the scene full of confidence if not yet fully armed commanding their turf if not yet sure of it. Their work was figurative but they were not realists, preferring the world of dreams and fantasy and filling their images with thoughtful, speculative poetry. One of the most gifted was Ed Carrillo whose beautiful draftsmanship and completeness of vision allowed him to blend pictorial fragments into incongruous continuities. Cabin in the Sky (1965) with its rambling red walls, sharp-cut tunnels and abrupt shifts from fanciful, evocative architecture to pure landscape, has the compelling reality of a dream retold by an impassioned dreamer. Carrillo’s work indicates an awareness of De Chirico and Bosch but his light-filled canvases and radiant, saturated color are uniquely his own. There is a mysterious but benign, almost pastoral tone to Cabin in the Sky with its giant seashells, the etheric shadow of a rabbit and full-lipped flowers creating abrupt spatial shifts against a background of architecture and landscape. It is an ambitious and successful work with a genuine spirit of self-exploration and revelation, an aura of naiveté which only serves to strengthen the impact of his vision.

Architecture plays a central role in many of Carrillo’s painting including Pearly Gates, (1965) an almost symmetrical two-part compositions with layered and bisected strata of masonry, carefully poised still life objects and disjunctive passages of landscape. Two round-headed arches fix the parallel axes of his work,one opens into a verdant field with prominently silhouetted trees and a distant mountain range , the other with its red and white striped columns gives way to a canal with docks and a distant mountain view. The two landscapes are impossibly discontinuous yet provocatively similar. In the foreground even more marvelous and impossible things occur. A red spiral contoured mound like an ancient Middle Eastern site appears in miniature echoed by a blue mastaba placed far to the front. On the other side of the painting we enter a big green pool of water. Carrillo’s vivid, self-contained colors suggest the conceptualized stylization and perceptual fragmentation of a primitive in whose work exactitude of parts mitigates against any smooth integration of the whole. However, the effect is to enhance has ability to evoke a works of the marvelous, the vivid and deliberately fragmented, all aspirations of early Surrealism. With Evolution (1962) his vision becomes darker and more narrative as death dances on the upturned feet of an acrobat and a birdlike creature lurks in a jungle setting full of tangled and threatened foliage.

There is nothing timid or commonplace about the lush floral imagery Joan Maffei whose paintings seem to press outward from the boundaries of their frames and project an otherworldly glow into the surrounding atmosphere. Symmetry and clarity of contour are important to her style, also vibrant evocative color asserting itself against darkened backgrounds. Moonflowers (1962)

is a fine and typical example of her work, an animated still life of invented flora pulsating with life. It is as though we are observing the silent, nocturnal erotic life of plants and thereby discovering a new and mysterious beauty. In 1961, just prior to her involvement with Ceeje, Maffei went to India on a Fulbright grant and that experience may have affected the emotional tone and color of her art. Viewing her work, one thinks also of Rousseau’s clearly delineated plants and flowers, the jungle in Yadwiga’s Dream with its resplendent undergrowth and compelling primitivism.

The visual compression and intensify that Maffei gives to commonplace subjects is evident in Portrait of Carlo (1966) in which a small boy with cowboy gloves riding a bicycle is transformed into a figure of awesome, almost mechanistic vigor, a startling, even frightening presence. Maffei’s imagery had feminist overtones even before the term was widely used, as in

I Told You So (1966), a painting so frankly sexual and emotionally searing that it eclipses many of the polemics and semi-clouded clichés of much recent feminist art. Her tondo formats, shaped frames and radial imagery exist to support the thematic content of her art, not as a conceptual strategy, feminist autobiography or as a physical advance upon the “objectness” of painting.

Assertive, shocking creations of nature are also to be found in the paintings of Ed Newell whose sharp-edged graphic outlines suggest cartoon characters gone astray even while his painter’s command of tone and wash bring them back again into the domain of art. His hybrid canine and feline icon loom large in the landscape like some 20th century counterpart of the icon-cats of ancient Egypt. In works such as Goddess (1959) they confront us, larger than life, clearly dominant and frightening. Newell’s work is aesthetic but impolite, fantastic to the point of excess, compelling and deeply memorable.

If their is a single significant style practiced by the core group of artists exhibiting at Ceeje, it must be the carefully wrought, homegrown Surrealism practiced by Carrillo, Maffei and Urmston. Others such as Bilker, Chavez, Garabedian, Lunetta and Richbourg had strong surrealist overtones to their art but their handling of pigment and preferences for asymmetrical and complex compositions set them apart from the obsessive, static centrality typical of the previous three. Urmston’s The Great Love Affair is an ambitious painting both thematically and technically. There is something reminiscent of Cranach’s painting of the Expulsion of Adam and Eve in the way Urmston’s male figure awkwardly covers himself and gestures to his mate, his hand movement a fascinating mixture of an ecclesiastical and a conversational gesture.

Numerous paintings exist within the larger composition, the framed with its Eden-like landscape and coiled serpent and the thrice-folded four-part painting placed on the table with its Biblical evocations of violent storms and strange primordial creatures. Almost everything about the painting suggests its sources in the Northern Renaissance so that the cubist construction of the figures themselves comes as something of a surprise. It has often been said that the art history program at UCLA had a genuine impact upon this generation of artists. As in Urmston’s The Great Love Affair this was not by direct imitation but a wry yet respectful feeling for themes that are timeless and multifacted.

If the artists of Ceeje were not immediately taken up by Los Angeles collectors and placed in national touring shows, they made the most of their position as outsiders and iconoclasts, frankly reveling in it. Self-parody was a common element in their art and to it they added a healthy ration of humor evident in the title of their 1964 exhibition “Six Painters of the Rear Guard: Garabedian/ Richbourg/ Urmston/ Bilker/ Chavez/ Carrillo.” implicit in their title and the work itself was a rejection of the kind of evolutionary abstract progressivism advocated by critics like Clement Greenberg and Michael Field. Los Angeles critic Henry seldis remarked of the exhibition, “Their work ranges from the lightly satirical to the nearly blasphemous.”

Perhaps the most memorable opening of an exhibition at Ceeje took place in the late autumn of 1965 when Lance Richbourg showed a cycle of paintings entitled “The Wild, Wild West.” The title was the same as that of a popular television program but Richbourg’s iconography was much more violent, intense and satirical than anything in the media, including Western films, comic books and popular novels which fed the subject matter of his art. On opening night a crowd of people streamed into Ceeje Gallery, many in Western costume and some in the pugnacious spirit expressed in Richbourg’s painting. At one point someone entered the gallery on horseback, causing an abrupt confrontation between art and life.

Richbourg’s vigorous, solidly three dimensional figures also rode on horseback, fought, made love, drank and died in his paintings, his themes a caricature of the romantic, fictional American West. His protagonists had the heavily muscled bodies of figures by Benton and the brilliant, at times lurid, color of films or magazine

illustrations, but Richbourg was not satisfied with replicating Western clichés in subject or style. As Henry Seldis observed quite correctly, the work is “related and removed from Pop Art.”7

Richbourg’s heros often enacted their life and death scenes in the presence of painted dreamscapes as a cowboy’s life seemed to pass before him in his final moments of agony. In One Eyed Jack (1965) a three way shoot out is so tightly and precisely staged in a moonlit barroom that it suggests art imitating art. The real irony and surface braggadocio of Richbourg’s subject matter is so interesting as to almost divert attention from the excellence and vigor of his drawing, so fulsome and personal in style that it lends its own special vitality and rhythm to the work. Richbourg’s desire to depict the mythic, historical and fictional West is all the more surprising if one considers that Southern California in the 1960’s was more often characterized and experienced as a land of sun, surf and beaches.

Other artists at the center of Ceeje’s activities were Roberto Chavez, Louis Lunetta, and Ben Sakoguchi, each creating an entirely personal structure and syntax for himself. Chavez’ work had a brusque, painterly directness , as in Group Shoe (1962)

his group portrait of Garabedian, Chavez, Carrillo, and Lunetta, a moving depiction of the strong, plainspoken qualities of character they admired. Lunetta balanced the natural decorative beauty of his art against his desire for strength of form and subject. A three-year stay in Ghana and his serious study of Asian art and culture contributed to the intricacy of his frieze-like figural compositions, complex all-over patterns of imagery and his preference for nonwestern subject matter. His was an unlikely counterpart to the art of Richbourg or Chavez but one could see and understand that lunetta’s work came from an earthy, almost primitivist aesthetic which found beauty amidst the ruggedness of man and nature. Ben Sakoguchi’s dense, kaleidoscopic paintings gathered the potent and unforgettable images of the 1960’s and also the ordinary, trivial ones top form a tapestry of sensory impressions and memory deeply evocative of that time. Sakoguchi’s work chronicles the cool glamour of the period, our fascination with the cultural life of European cities, the rapid-fire assault of media images which became not only a daily but a minute-by-minute occurrence in urban areas such as Los Angeles. The fashions have changed a great deal since then and Sakoguchi’s hard-edged style of rendering is also typical of the 60’s, but his record of the visual and social landscape is one of lasting interest and value. So complete and accurate was Sakoguchi’s grasp of his own perceptual field that he even seems to include fragments of paintings seen at Ceeje, as in the rambling brick walls so typical of Carrillo and the splendid jungle flowers of Maffei.

There were several among those exhibiting at Ceeje who did not project a realm of fantasy but preferred to find other subjects in the real world of tangible objects. Aron Goldberg’s still life compositions appeared at first to be images of quietude and serenity. Upon closer examination, his table top still life images in calm grays, tan and other soft tones contained the severed parts of animals as a mealtime offering served up on familiar pieces of crockery. In a recent reminiscence of Ceeje, Goldberg stated that it was his desire and one he shared with some of his contemporaries to “see the world as new-made, full not of artifacts of culture, but objects of desire and fear.”8 It was typical of them to find aesthetic and emotional value in subjects and visions commonly held to be grotesque, humorous or inconsequential.

Maxwell Hendler showed several small still life compositions at Ceeje in the early ‘60’s. These everyday tabletop worlds of cracker and cereal boxes, plates and jars were so lovingly and painstakingly rendered that they anticipate, at least on this coast, much of the innovative style and content of photo-realists art and do so with a resonance of feeling seldom found in that style.

Ceeje even had its own counterpart of Henri Rousseau in the colorful persona of retired Italian pastry chef, Marcel Cavalla, who enjoyed the camaraderie of many of the artists in the gallery. Self-taught and eager to depict the burgeoning population and changing environment surrounding his residence in Bunker Hill, Cavalla filled his canvases with topographical detail, daily events and personal fantasies which transformed and animated everything he painted. He proved a popular addition to the gallery. In 1962, his first one-man show sold out. That very week the editors of Life magazine were doing a story on the rash of sell-out exhibitions and Cavalla ended up on the pages of Life in the company of newcomers Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns.

Any gallery, while devoted to the exhibition of works of art and to the development of the careers of its artists, is ultimately the creation of its owners-directors. In the case of Ceeje it was a collaboration between Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome. In an effort to find a national audience for their artists they opened a second Ceeje Gallery in New York in 1966 at 19 W. 57th Street. It lasted two seasons. Their lively curiosity and generous spirit was evident in the program of Ceeje and, happily, they have retained that enthusiasm for their artists and for those of our own time as well. It is to recognize their role in the artistic life of Los Angeles and to enable us to look again at the marvelous, irreverent, thoughtful and important art produced by their artists that this exhibition is being held.

Footnotes

1. William Wilson, “Garabedian at Ceeje,” Los Angeles Times, April, 1965

2. Interview with Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome, Agua Dulce, California, October, 1983

3. Henry Seldis, “Four Painters at Ceeje,” Los Angeles Times, July 20, 1962

4. Interview with Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome.

5. William Wilson, “Garabedian at Ceeje.”

6. Henry Seldis, “Six Painters of the Rear Guard,” Los Angeles Times, April, 1964.

7. Henry Seldis, “Lance Richbourg at Ceeje,” Los Angeles Times, October, 1965.

8. Aron Goldberg, “Reminiscence of Ceeje,” unpublished manuscript, 1983.